ELOQUENCE: The Furniture of Seth Janofsky

Seth Janofsky, once a studied photographer, has a passion for woodworking that has developed into an artistry. His designs and workmanship are truly incredible. Janofsky has the ability to take his two-dimensional ideas on paper and turn them into three-dimensional pieces of art. Though his pieces are works of art, they are not meant to be simply observed in their beauty. Janofsky’s furniture is not the type of art guarded by “Do Not Touch” signs, but rather openly welcomes you, and asks you to welcome it into your life.

“The primary purpose of art, I think, is not self-expression but communication – about what it means and feels like to be human. Self-expression is a by-product. Art is not some free-for-all, but an endeavor that can be usefully defined. Art, we might say, is the communication of important things by eloquent means. Great art is the communication of very important things by very eloquent means. The problem of the artist is not, as some seem to believe, to figure out how to do whatever he or she wants to do, but rather to find the way to do what seems truly worth doing, or needs doing. There is a difference.

I, like many others, find the serenity of traditional Japanese design and architecture and its insistence on the investing of simple objects of use with both beauty and human relevance-very appealing.”

**Photos courtesy of Woodwork: A Magazine for All Woodworkers February 1999; photography by Glenn Gordon.

Comments of Seth Janofsky on his art

Like most woodworkers interested in studio furniture making, I came early on in my woodworking experience into contact with various aspects of the Japanese woodworking tradition. The ubiquity today, here, of Japanese tools and interest in techniques of joinery makes it almost impossible that this should not be so.

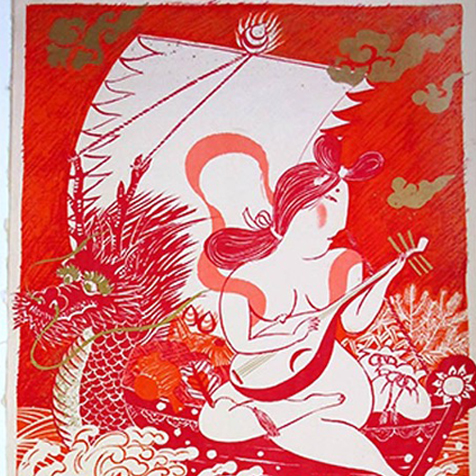

But the much greater influence from the Japanese on my woodwork is more on the aesthetic, or spiritual, side, than on the technical. My background in the visual arts, before I devoted myself entirely to craft work, as well as my natural inclinations, provided me with a great admiration for other Japanese art and craft work, in particular screen-painting, lacquerwork (makie), textiles and ceramics. The vision we get of the way these arts, and their products, were integrated into the traditional Japanese lifestlyes, of the kind of objects made to be lived with, and of the deep appreciation for their various qualities have impressed me profoundly and helped to shape my aims as an artist, really much more than anything to do with Japanese wookdworking techniques per se.

I, like others, find the serenity of traditional Japanese design and architecture, and their insistence on the investing of simple objects of use with both beauty and human relevance, very appealing and take from my knowledge of them what I can that serves my artistic and human purposes.

I am not a Japanese furniture-maker, nor do I make Japanese furniture. But people remarked on a Japanese spirit in my work, even before the Japanese aesthetic entered into it in an explicit way. I think of myself as a contemporary, Western furniture designer and craftsman, but certainly I have tried to bring some Japanese qualities to my work. Initially this was reflected primarily by an emphasis on simplicity and quietude in the work, but my recent work has borrowed very deliberately certain Japanese aesthetic devices, and has involved an attempt to fuse my interest in surface decoration and the abstraction of natural motifs into patterns, in the Japanese manner, with the essentially Western furniture that I make.

My most basic artistic goal, however, remains simply to make the best things I can, according to all that I know about things, and what makes them good.

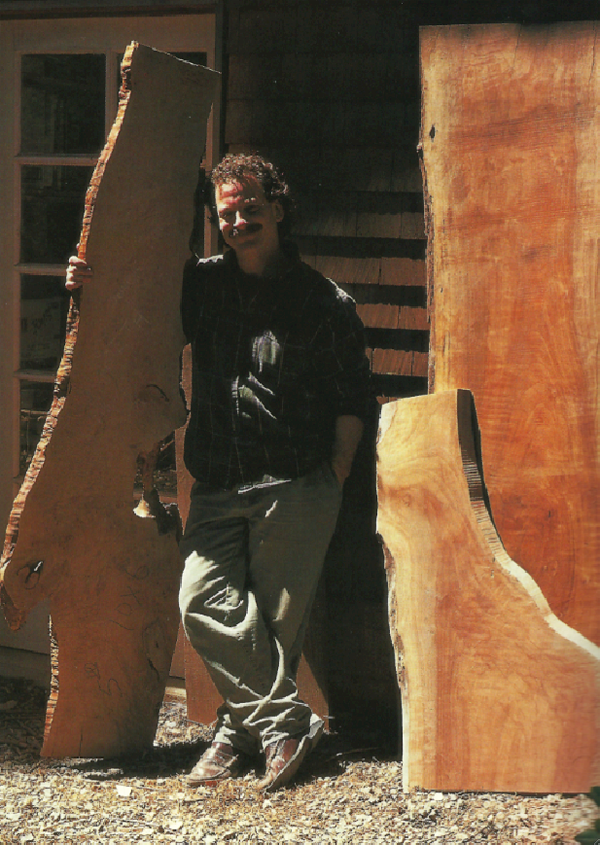

At right: Janofsky with a trio of flitchcut planks. Janofsky’s sketchbooks contain drawings for works that make use of the “free edges” of planks sawn through and through like these. The edges seen in this picture might well appear in some future work.